(Ohtsubo branch of Owari Line, Yagyu Shinkage Ryu)

copyright © 2008 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved.

This article is the pivotal first interview with Kajitsuka Yasushi Soke, headmaster of the Ohtsubo branch of the Owari Line of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. Here, Kajitsuka Sensei shares with our readers the important and fundamental ideas about this most renowned of Japanese sword styles. Those interested in this branch of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu can consult his group’s website: Arakido

Kajitsuka Sensei with Mr. Tong in Yokohama (2008)

Kajitsuka Sensei with Mr. Tong in Yokohama (2008)

Author’s note: This interview was conducted on July 23, 2008 in Kagurazaka, Tokyo. While Kajitsuka Sensei does speak some English, the interview was conducted mostly in Japanese. We were assisted by two of his students, one Japanese and one American, who helped out with interpretation at points where the Japanese was too complex for me. I have thought it best to try to preserve what he told me directly as he said it, which he did in both Japanese and English. At various points through the interview transcript presented here, I have added a few notes that may help readers as to what Kajitsuka Sensei might have meant. Any errors in interpreting what Sensei has said are entirely my own. I hope that readers will find the reading enjoyable nonetheless.

My thanks to the many people who helped to make this interview possible and who assisted in its realization: Mr. Jack Hathway, Ms. Sawada, Mr. Kazunori Yoshioka, Mr. David Kawazu-Barber. Of course, my sincere thanks go to Kajitsuka Sensei for his endless patience and his generosity in allowing me to interview him at length about his art and his thoughts.

__________________________________________________

Part One: The Nature of Japanese Swordsmanship

Question: There is still some confusion about what exactly is “kenjutsu”. What is “kenjutsu” and how is it different from kendo or iaido?

Sensei: Kenjutsu means fighting with swords. But in old days, we were not just fighting with swords. We fought with bo, spear, bow and arrow, and other weapons. When you lost these weapons on the battlefield, then we used the sword. After you lost your sword, then we used jujutsu.*

(*Kajitsuka Sensei also teaches Yagyu Shingan Ryu taijutsu, which has a jujutsu component which focuses on unarmed fighting techniques used while wearing full armour)

In the old styles, styles were composite, all-encompassing – not just sword. In old days, kenjutsu was just one of the parts. **

(** here Sensei may be referring to old styles like Katori Shinto Ryu for example which contain study in a variety of weapons like spear, naginata, bojutsu, shuriken, etc…and even include a program in jujutsu)

Naginata

Naginata

In the Sengoku Jidai*, the sword was only a tool, like any other weapon.

In the Edo Jidai*, the peaceful era, the katana became more than just a tool. It became a symbol and an image. The sword became a personification. The sword also became indicative of status; it became a status symbol.

(* the Warring States Period (1467-1600) was a period of civil war and political intrigue where various clans fought to gain control of the country. The Edo Period (1603-1868), established by Tokugawa Ieyasu once he defeated his rivals and gained control of the country, was a period of political stability lasting 250 years.)

In the Edo Jidai, then we see the emergence of only kenjutsu styles. In the era of peace, we start to see the separation of the military arts. Specialization began. So gradually we have styles that focused specifically only on sword.

In the Meiji Jidai, wearing swords was banned and so the fighting arts gradually disappeared. Some were saved from extinction in three ways:

1) the police saved some and kept them intact (e.g., kendo)

2) some became showcases for performance, like performance arts**

3) some evolved into sports (e.g., kendo, judo)

(** kyudo(Japanese archery) or yabusame (archery on horseback)?)

So traditionally kenjutsu is simply the art that focuses on how to fight with sword.

Question: In your opinion, what is the Japanese way of swordfighting or swordsmanship?

Sensei: In old times, kenjutsu was not thought of as anything special. Only in the Edo Period did it become a personal thing*.

(* I think here Sensei is referring back to his idea of the sword and sword study gradually becoming a personification of ideas and ideals)

In old days, it was about strength and pride and emotion only. Example: “I am the strongest” and so I prove it.**

(** an interesting idea. Would seem to fit with the idea of the Civil War Period being a time of civil unrest, incessant fighting, political intrigue with themes of allegiances, betrayals, vengeance and revenge, etc… Life was not as cultured as in later, more peaceful eras.)

Before, it was about my pride. It was about being the strongest.

But with the Edo Period and the new Shogun, the sword became something to further yourself. The sword became the way to grow a soul.

It became not about killing people. It became about promoting life.

Swordsmanship became about saving yourself.*

(* this brings to mind exactly the plot of Director Hiroshi Inagaki’s acclaimed epic Miyamoto Musashi (renamed Samurai Trilogy in North America) which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1955).

Musashi (Mifune Toshiro) and Otsu (Kaoru Yachigusa) from the gorgeous film Miyamoto Musashi (1955)

Musashi (Mifune Toshiro) and Otsu (Kaoru Yachigusa) from the gorgeous film Miyamoto Musashi (1955)

Question: What exactly do you mean when you say that Japanese swordsmanship became about promoting life?

Sensei: Kenjutsu was originally just a way to kill people. Learning how to kill people. Techniques for killing.

But in the Edo Period, the thinking evolved. It was not just a set of techniques anymore. There was a philosophy in the technique. Hidden things, like how you act, what you do. It became concerned about mannerism. There is a deeper meaning.

You learn a martial art so that you don’t need to use it. Using kenjutsu to promote life.

Yagyu Munenori prepared the Heiho Kaden Sho for the Shogun for the next peaceful era.*

(* Yagyu Munenori was appointed the official swordsmanship instructor for the Shogun and his family, the highest and most glorified position in the land, a position coveted by many professional swordsmen.)

For the Shogun to promote to the people, to teach the people as His way.

Shinkage Ryu is not a technique** for you to win.

It is a technique so you don’t lose.

(** here, Sensei says in English “technique” but he may mean other concepts like “art” or “Way”)

I will tell you about two types of sword:

1) “katsu ken” (literally “victory sword”): sword for winning and killing. But when you kill them, there will be hatred left behind…

(* leading presumably to unending strife. Revenge upon revenge without end?)

2) “makenai ken” (literally “cannot-lose sword”): instead of leaving hatred behind, it leaves a curiosity behind. Because you do not win but you do not lose, there is a sense of respect left behind.

Hence, promoting life…

__________________________________________________

Part Two: Yagyu Shinkage Ryu and The Living Sword

Question: Please tell us about your branch of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu.

Sensei: Shinkage Ryu was founded by Kamiizumi Hidetsuna*. He had studied Kage Ryu and also Shinto Ryu**. From the two, he created Shinkage Ryu.

(* later he changed his name from Hidetsuna to Nobutsuna.)

(** Katori Shinto Ryu is also known simply as Shinto Ryu in Japan.)

He had three students: Hikita Bungaro, Marume Kurando, and Yagyu Sekishusai*.

(* also known as Yagyu Muneyoshi.)

Hikita Bungaro created Hikita Shinkage Ryu and Marume Kurando founded Taisha Ryu.

Yagyu Muneyoshi taught his son Munenori* who founded the Edo-kei (Edo Line) of Shinkage Ryu.

(* Munenori was the author of the Heiho Kaden Sho, the famous treatise on the Yagyu style of swordsmanship which saw the incorporation of Zen philosophy with swordsmanship.)

Yagyu Munenori, who made Yagyu Shinkage Ryu famous when he was appointed the official teacher of swordsmanship to the Shogun.

Yagyu Munenori, who made Yagyu Shinkage Ryu famous when he was appointed the official teacher of swordsmanship to the Shogun.

Munenori was succeeded by his son Mitsuyoshi** and after him, came Yagyu Munefuyu. However, after him, the Edo Line died out.

(* Yagyu Mitsuyoshi was also known as Yagyu Juubei, a popular and romantic figure in samurai folklore. Mitsuyoshi wrote a book on swordsmanship entitled Tsuki no Sho, in which he interpreted all the secrets handed down by word of mouth through three generations – from Kamiizumi Nobutsuna to Muneyoshi to Munenori)

However, Muneyoshi’s grandson Yagyu Toshitoshi established the Owari-kei (Owari Line), which is based near Nagoya. This line has continued until now. When Yagyu Gencho was the soke, he had many students. Of course, he passed the style onto his son Nobuharu who passed away recently. The style now rests with Nobuharu’s son Yagyu Koichi. But Gencho’s other senior students also taught. One of them was Ohtsubo Shihou. My teacher Mutoh Masao succeeded him.

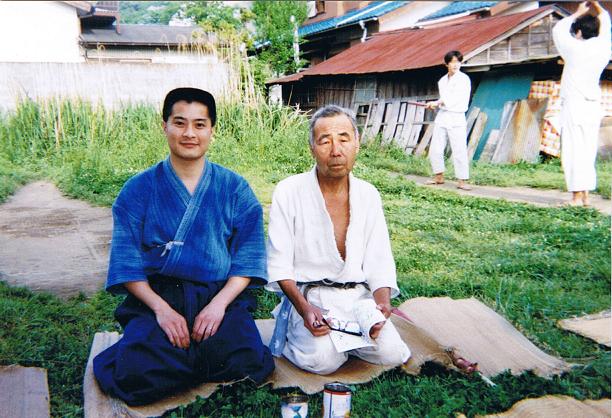

Mr. Tong with Mutoh Sensei discussing the Heiho Kaden Sho.

Mr. Tong with Mutoh Sensei discussing the Heiho Kaden Sho.

Question: Other types of swordfighting like Chinese styles or Western styles seem to have many exchanges of blows. Japanese sword styles typically seem to rely on one cut.* Why do you think this is?

(* Yagyu Shinkage Ryu has gasshi-uchi, Kashima Shinto Ryu has hitotsu tachi, Itto Ryu has kiri-otoshi, etc… all of them espouse the ideal of the one perfect cut.)

Sensei: I think because in a real fight, the simple technique works best.

(at this point, Sensei draws some kanji on a piece of paper)

We have an expression. It is called “hakka hisshou“, which means “8 directions, guaranteed victory“.

(Sensei then draws on a piece of paper 4 lines intersecting at a central point like a compass, so that there are 8 points: N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW)

No matter from which direction they come, if you cut straight, you will win…

The difficult thing is if THEY cut straight. Then this is a problem.

Question: We get the idea, which we see in Japanese movies like Seven Samurai, that swordfights do not last very long (for example, the fight scene in the town between the silent, stone-faced samurai Kyūzō and the braggart). Usually the affair is finished in one cut. Why do you think the Japanese swordsman’s mindset embraces this idea of “one cut”?

The pivotal first fight scene between the braggart and Kyūzō in the famous film Seven Samurai (1954)

The pivotal first fight scene between the braggart and Kyūzō in the famous film Seven Samurai (1954)

Sensei (smiling): Because it’s “cool”.

(there is laughter around the table)

Question: Is the “one cut” important in your style?

Sensei: It is the most basic cut but it is the most difficult to achieve perfectly. This is a fundamental principle: the most simple is the most difficult.

Question: In many sword styles, there is an importance placed on kamae. Is kamae important in your style?

Sensei: In other styles, yes, there are kamae. In Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, there is no kamae. It is free moving.

Question: No kamae?

Sensei: Yes. There are two types of styles: setsuninken and katsujinken.

Setsuninken is a killing sword and these styles usually have kamae.

Katsujinken is a living sword. This type of style has no kamae.

Question: Can you explain in more detail?

Sensei: In the killing sword styles, I dictate the circumstances so that you will die. From my kamae, I force you to do something. The kamae is also a defence shield that keeps me safe.

But even better is not to have kamae. At higher levels, there is no kamae. You are then very flexible. The goal is to be free from kamae. Not limited.

Mr. Tong is pictured here in “mu-gamae” (literally “no kamae”). In other words, “no-stance” or “empty stance”, the stance of no-stance.

Mr. Tong is pictured here in “mu-gamae” (literally “no kamae”). In other words, “no-stance” or “empty stance”, the stance of no-stance.

The living sword or technique means freedom.

The dying* sword or technique means limitation, like a forced action.

(* or killing sword)

The living sword or technique means freedom because it has its own movement. It is not limited. It has freedom of action and freedom of purpose. It is like a living animal.

The dying sword or technique means limitation because it is like having only one road to travel down. There is no choice. For the opponent, that is all they can do. They are forced into one action and we are forced into one action. It is like a dead animal.

Therefore, the concept of katsujinken, the living sword, is an idea that covers all techniques in this style, like a blanket. It influences everything we do.

Question: Why was the style named Yagyu Shinkage Ryu?

Sensei: Actually, only outsiders call it Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. We call it simply Shinkage Ryu. But outsiders need to distinguish it from other styles and since it was the Yagyu family style, naturally the name came about this way.

Shinkage Ryu came from the fusion of Kage Ryu and Shinto Ryu, both of which Kamiizumi Nobutsuna studied. Essentially, it means the “new Kage“ style.

Question: Is there any other significance to the name?

Sensei: Yes. Kage means shadow. Why shadow?? A shadow doesn’t create its own movement.

Whatever you do, your shadow follows… or reflects.

So whatever my opponent does, I follow and react. I base what I do on what the opponent does.

Like his shadow…

Question: Would you say that Yagyu Shinkage Ryu is focused more on attack, defence, or counter-attack?

Sensei: None of them…. and yet, all of them.

With no kamae and the consequent freedom of movement, it’s all of them.

It depends on what the opponent does and subsequently, what you need to do.

Question: In your opinion, what makes your style unique among sword styles?

Sensei: It was presented to the Shogun. It became representative of the Shogun.*

(* and the Shogun’s new policy)

That’s why it’s famous.

There were many styles that fought for that position but the Shogun chose this style due to the similarity of thinking** and philosophy between the Shogun and the Yagyu style of swordsmanship.

Yagyu Shinkage Ryu: The Shogun’s sword style

Yagyu Shinkage Ryu: The Shogun’s sword style

(** Here I will quote an excerpt from Makoto Sugawara’s excellent book that demonstrates this relationship between the Shogun and Munenori:

“Perhaps the strongest principle Munenori tried to instill in his disciples was that swordsmanship was not a skill learned to kill people but rather to fully realize one’s personality, one’s inner being. This concept also played a pivotal role in strategy. Although Munenori had not yet incorporated Zen Buddhism into his swordsmanship during the years he instructed Tokugawa Hidetada, his every move seemed oriented in that direction. To Munenori, swordsmanship was far more than the art of developing fencing techniques; it was life itself, for it trained man to develop his inner self. By training with Munenori, therefore, Shogun Hidetada was learning the essentials of statecraft through swordsmanship.”

Source: Sugawara, Makoto, 1988. Lives of Master Swordsmen, The East Publications, Tokyo, Japan. pp.126-127.)

Question: Can you explain what you mean by “it became representative of the Shogun”?

Sensei: One part in Kage Ryu is that you don’t need a sword. This was developed further in Shinkage Ryu.*

(* the concept and technique of mutō, or “No-sword”.)

You can still not defeat an opponent and still not lose.

Not winning but not losing.

In the Edo Period, not a lot of people were carrying swords**, so a style that doesn’t rely on a sword was needed by the Shogun for the bakufu, for the politicians and the officials to keep the peace, without bloodshed if possible.

(** The Edo Period was an age of peace and political stability. Peace saw the rise of towns and cities and the urbanization of the general society. Swordsmanship became less and less concerned with battlefield fighting and reflected more concern with the urban scenarios (i.e., ambushes, fighting in houses or in the street) and circumstances (i.e., on a hardwood floor, on a level road) that swordsmen would most likely encounter in daily life.)

With the imagination of having a sword, you can defeat an opponent. The sword is not vital. It is just a tool.

Question: In your opinion, what is the fundamental philosophy or idea of budo?

Sensei: In the old styles, the techniques are of course important. But everyone knows the techniques. They have not changed*.

(* i.e., they have been codified and in a sense, are immutable.)

But from now on, finding something new is important.

Let’s take the word “kobudo”. What we do is classified as kobudo. It is formed of these kanji (writes the kanji for “ko”, then “bu”, then “do”, that make up the word). “Ko” typically means “old”. Old usually implies dead, a dead art. But it is not old. It is not dead. It is still alive, today.

I don’t like the term “ko”-budo. It is not dead. It is still living. It is still adapting. It will continue to live and it will adapt to the needs, demands and atmosphere of the times in which it finds itself. It adapts constantly.

So, don’t be afraid of new things or trying new challenges or experiences. This is the essential spirit of budo.

In Japanese, we talk of “challenge”*.

(* here, Sensei uses the Japanese phrase “cha-ren-ju”, coined from the English word “challenge”, which has a little different meaning when used in Japanese.)

This means about the spirit of striving and reaching for greater things, greater heights.

Budo has survived by adapting to each era. To continue to survive, it has to adapt and keep adapting.

All styles that stopped adapting, have died out. The Edo Line of Yagyu is no more, unfortunately. This is a prime example.

Question: In your opinion, what is the fundamental philosophy or idea of Shinkage Ryu, or maybe of your Line of Shinkage Ryu to be specific?

Sensei: Our fundamental philosophy is to adapt and change. Change is important.

Well, maybe “change” is not the correct term. Because change has the nuance of eliminating something and replacing it with something else, something new.

“Adapting” is a better word. It means adding to, modifying, to fit new situations and circumstances.

If you don’t adapt, if you just change, then you become like mixed martial arts. Replacing something with something different. You lose the original meaning, the original purpose, and the original spirit of budo.

We don’t want to replace. Rather, we strive to adapt…

__________________________________________________

Part Three: Teaching and Learning

Question: As a teacher, what do you try to teach your students, apart from just technique?

Sensei: I try to teach my students three rules to live their life by:

1. Love what you do. This is the most important.

2. Do it from the heart. We say “kokoro”. In other words, do it with all your heart and soul.

3. Continue it. Keep doing it. Don’t stop.

These are the three main rules.

Now after these three, I also recommend to my students two more:

4. Don’t be afraid.

5. Take things on. By this, I mean, try new things. (The Japanese word, “Challenge”.)

Mr. Tong with Kajitsuka Sensei and members of Arakido in Tokyo (2008)

Mr. Tong with Kajitsuka Sensei and members of Arakido in Tokyo (2008)

Question: As a teacher, what do you believe is most important for students to remember when studying kenjutsu (or budo)?

Sensei: Ah, an interesting question. I would like my students to remember that everyone is the same. There is no student. There is no teacher.

Question: There is no student, there is no teacher??

Sensei: Yes. Everyone is the same. There is no student. There is no teacher. Of course, there is still teacher status but that is all.

Question: I am not sure I understand.

Sensei: Here is an analogy. Budo is like climbing a mountain. Everyone is climbing up the same mountain. I am just farther up the mountain than you. I have seen the path that you will take. So, I can point out some of the pitfalls that I have already encountered on my journey up this mountain.

However, you must realize that I am still myself going up this mountain.

But, I am not a guide telling you where you should go. We are all mountain climbers in the same group. But there are, naturally, some of us with more experience than the rest of the group…

(at this point, the American interpreter gives his interpretation of what Sensei has just told us: “Sensei is saying that he is not teaching us. He is passing on what he has learned and experienced in his years of training.”)

Question: That is a great analogy. Thank you Sensei for your time and generosity in allowing me to talk to you about many things in budo. It has been a great session.

Sensei: Not at all. It is my pleasure.

__________________________________________________

Author’s post-script:

I had the wonderful good fortune to have studied under Mutoh Sensei, a very kind and warm man. He welcomed me kindly and taught me honestly. Mutou Sensei was a great teacher: patient, understanding, and encouraging.

Now I have had the good fortune to have met and studied under another great teacher, Kajitsuka Sensei. His frank and open attitude made me feel accepted and his teaching style was very much like Mutoh Sensei’s before him: patient, understanding, and encouraging. I must confess that I was very impressed when studying and talking with him in Japan. He is full of knowledge and wisdom but most impressive was his enthusiastic spirit: enthusiasm for his art, enthusiasm for teaching, enthusiasm for life.

“Don’t be afraid to try new things.” He is truly inspirational.

__________________________________________________

This interview was previously published online through EJMAS. Click on the links below to access each part of the interview.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3