Seminar Report

April 2019

Ottawa, Canada

copyright © 2019 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved.

__________________________________________________

In April of 2019, Tong Sensei travelled to Ottawa to conduct a private seminar on the roots of kenjutsu. Below is copied the seminar report courtesy of Meishinkan Dojo, our official keikokai in Ottawa. We have also included our own commentary to support the text and add further details to the story.

__________________________________________________

The connections between fundamentals: a seminar summary

copyright © 2019 Erika Gaal, all rights reserved.

Over the last weekend in April, we had a unique opportunity to travel to the past with Tong Sensei and explore the roots of Japanese swordsmanship. We had people from different disciplines participate in the seminar- Iaido, Jodo and Kendo being the predominant arts and also some experienced with historic koryu schools like Kage Ryu and Niten Ichi Ryu. And being that Yagyū Shinkage Ryu is our focus at Meishinkan, we all had many revelations that gave us further insight into our primary martial arts.

We started the first day of the seminar working with bokuto. We learned some basic Kamae and focused on our form as we practiced the cuts and movements within kata. It has been said time and time again that focusing on basics creates a strong foundation in martial arts, and that things like posture, strong stance and being balanced on your feet are what determines how effective your technique will be.

If we think about the body movements (tai-sabaki) involved in Kuka-no-tachi we can see how important the placement of your body weight becomes, as we move through our kurai and from one position to another quite quickly. If you have too much forward weight as you strike and then have to move backward to get out of distance you will find it causes a lag in the time it takes for your body to avoid being struck. Another important factor in how quickly and smoothly you can move is having your knees bent. Having a lower stance allows more fluidity in your steps and aids in keeping you lighter on your feet. These things that are referred to as basics need to be revisited continuously and kept at the forefront of our minds during our practice, as this will help us reach the potential we are each capable of. One could argue they are not actually basics, but the secrets to success in Budo.

Throughout the day we explored the history and lineage in which different schools originated, and in doing so I was able to see clearer connections between them through shared movements and technique. In having practiced more recent arts like MJER Iaido, SMR Jodo and Kendo, I saw some of their techniques in what could very well be their original form. When we take into account the natural evolution of things, we can see where something originally designed for armour transforms over time. For example if we look at Yagyū Shinkage Ryu’s migi and hidari gedan, it is a very advantageous position as there are many ways to attack from it. You can easily cut upwards to attack the opponent’s wrist, which originally would have been one of the few unprotected areas on the armoured samurai. So one could suggest the origin of that stance came from an older art designed for the battlefield.

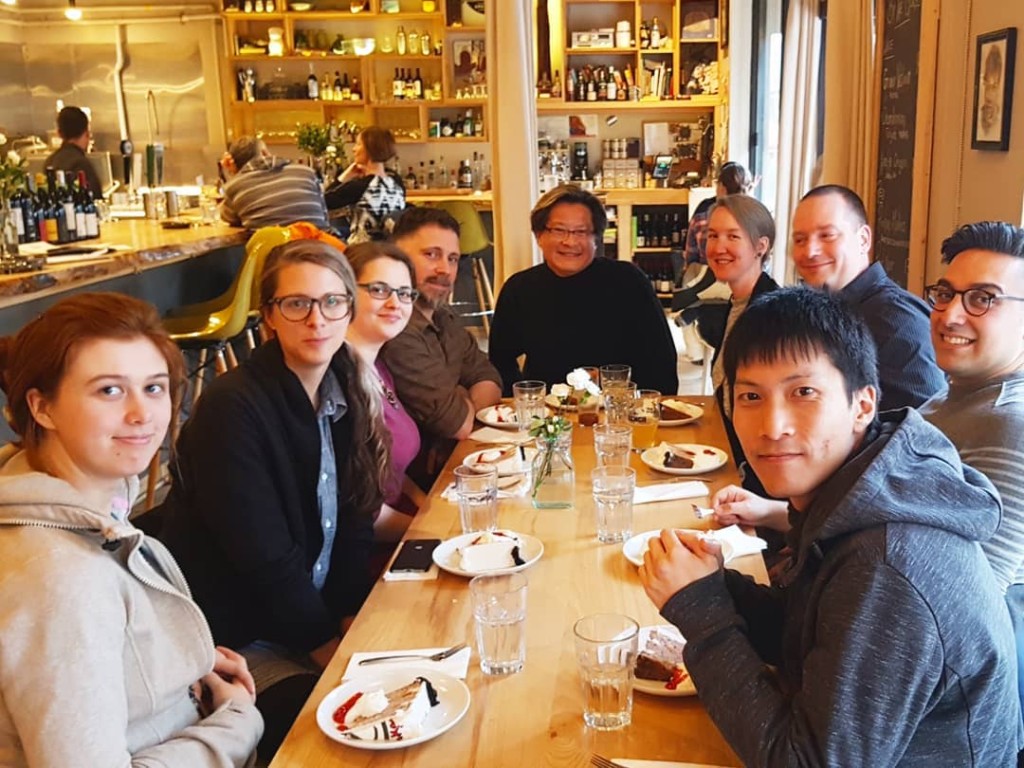

After the day’s training was done we all went for dinner and celebrated the dojo’s one year anniversary. These times where we gather outside of the training hall are precious, and contribute to the bonds the group members form and the sense of community that is inevitably built over time and dedication to the art. There is a unification that occurs between people that share a common interest, and that unification breaks down borders that might otherwise be guarded. Here we were all able to enjoy one another’s company and conversation, despite different backgrounds and lifestyles. One of the things I always appreciate is how at these times there is no rank, and even Sensei is comfortable just being part of the group.

The next day we explored weapons of different lengths, starting with Kodachi. For those that are familiar with using the length of the sword, this posed a new challenge as you have to be willing to get in close to your attacker. Even here I saw connections. We use Tsuke noru to catch and suppress a sword’s cut by catching the right wrist of the swordsman, and when you are using a short sword this is a very useful tactic. Again, you have to be willing to move right into the danger zone to gain the full effectiveness of the suppression, and with a Kodachi moving in close is one of your only options. I can see how certain things carry over into other weapons too, as you can only manipulate a body in so many ways.

Body mechanics were a prevalent theme throughout the weekend. As we experimented with different hip positions and lower and deeper stances, we also learned a deeper understanding of the pressure we apply to our weapon and how it translates to the weapon we are making contact with. There is a certain ‘feeling’ you get, a communication of sorts, that happens through the crossing of swords. If you use too much pressure this communication is lost, but with soft and continuous contact you can feel and even anticipate your opponent’s next move. We see this in the kata Usen Saten very clearly, where if Shidachi applies too much pressure while pushing Uchidachi back it is easy for them to attack the opening you cause in doing so. There is a disconnect that Uchidachi can take advantage of. That ‘connection’ is a crucial part of kata, and creates the conversation between both participants that we are to learn from.

It makes it cohesive and fluid, and resembles a wave in the ocean- you flow in and flow out. When practicing Enpi you feel this wave, while connected to your partner you both flow back and forth towing the other with you as if tied by a string. It’s an experience that once you feel, you see in the other kata you practice. I feel Enpi is a pivotal kata for Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, as it embodies the lessons you are to apply to the rest of the curriculum. Over the weekend, through practicing older techniques I understood where these lessons may have come from, and this is something that simply can’t be learned through a book or video- it must be felt.

There are different ways to learn the lessons within a particular school, one of them being by ‘heart to heart’. This is where it is transmitted by mouth and experience from Sensei to student, and these lessons can only be taught this way. Sometimes in order to truly understand something we need to feel it, we need to experience it. And when we are fortunate enough to access these opportunities our minds expand and we gain greater insights.

Everyone left the seminar with new skills and a deeper understanding of the sword. It was a memorable weekend, and I am grateful to everyone that contributed to making it that way. Tong Sensei continues to share his wealth of knowledge with us, and every time I am left in awe of how much there is to learn about these wondrous and enlightening arts. I continue to be left with an enriched soul and an ever growing love for this path I’m walking.

Thank you Sensei, for sharing your time and spirit with us.

__________________________________________________

Tong Sensei’s Commentary:

Everything comes from something else. Nothing is created out of a vacuum or thin air. That is why lineage is so important. Our art is Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. But Yagyu Shinkage Ryu came from sword styles that existed before it; namely, Katori Shinto Ryu and Kage Ryu.

So this seminar was a good chance for our students to have a glimpse into the roots of our art. Some of the kurai like hiza-sha, hasso, and sha came from older kamae like migi-gedan-no-kamae, in-no-kamae, and sha-no-kamae. Some of the evasions come from older versions found in these older styles. Concepts like jūmonji come from these older styles; they are just expressed differently. Specialized techniques like grabbing the blade found in Enpi, which the 21st Headmaster said is a very old form, actually comes from the Gogyo set of sword katas of Katori Shinto Ryu.

Ni-no-giri resembles yokomen-uchi. The raking movement of kamuri-irimi from Katori Shinto Ryu shows up near the end of Enpi, while the technique of o-gasumi appears as an upward cutting technique in the third section of Enpi called Yamakage.

It is common knowledge that the techniques and tactics found in this special kata Enpi were designed to defeat the Gogyo techniques of Katori Shinto Ryu. So, with all these instances of the influence of Katori Shinto Ryu on the techniques and tactics of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, it makes sense that exploring some of the ideas of Katori Shinto Ryu would be a very fruitful exercise.

The purpose of this seminar was quite simply to expose our students to the ancestor art of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, so as to give them a better understanding of where some of the Yagyu techniques came from; in other words, they need context. The thinking was that if you know where they came from and what their original purpose was, you can come to understand how they evolved into what we see in Shinkage Ryu.

Katori Shinto Ryu, created in the Sengoku Jidai (The Warring States Period), is a style born in the era of battlefield fighting where the fighting tactics and techniques focused on defeating armored opponents. Questions in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu like why we stand in hanmi, why seigan is such an important position, why the deep stance, all trace their answers back to the era of what Yagyu practitioners coin as ‘kaisha kenpo’ (armored fighting). To get a better understanding of why things developed into the way they are in Shinkage Ryu, you have to take a look at these older techniques and styles.

I wrote previously about this subject of the evolution of styles. Please read it here: Evolution

In closing, there are reasons for everything. From the smallest issues like how to hold the sword to grandiose philosophical ideas like The Life-Giving Sword, you need to examine how things evolved, where they came from and what they eventually developed into later on. It’s all about context.